The Role of Inflammatory Cytokines in Ovarian Cells During the Malignant Transformation of Endometriosis

Tuğba Çevik¹, Gizem Ayermolalı¹, Zehra Kanlı²,³, Burak Aksu4, Hülya Cabadak³, Tevfik Yoldemir5, Banu Aydın³*

¹Marmara University, Institute of Health Sciences, Department of Biophysics

²Marmara University, Nanotechnology and Biomaterials Application and Research Center

³Marmara University, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Biophysics

4Marmara University, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Medical Microbiology

5Marmara University, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

*Corresponding:

banuaydin[at]marmara.edu.tr – ORCID: 0000-0002-3267-8620

Received: 08th August 2025

Accepted: 21st September 2025

Published: 23rd September 2025

Abstract

Endometriosis is a chronic estrogen-dependent inflammatory disease characterized by the presence of ectopic endometrial tissue outside the uterus. Inflammation, angiogenesis, immune regulation, and hormonal signaling pathways play complex roles in its pathogenesis, and these microenvironmental factors are believed to contribute to malignant transformation. Particularly, clinical and molecular data support that endometrioid and clear cell epithelial ovarian cancers (EAOC) can originate from endometriotic lesions. Our central hypothesis is that estrogen and pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, VEGF, EGF, IL-10) within the endometriotic microenvironment facilitate malignant transformation by enhancing proliferation, angiogenesis, and intracellular signaling in ovarian cancer cells. To investigate this, Ishikawa endometrial cells were treated with estrogen and cytokines for 48 hours to create an endometriosis-like microenvironment, which was subsequently applied to OVCAR3 ovarian cancer cells.

Cell viability was assessed using the MTT assay, and levels of VEGF (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor), NGF (Nerve Growth Factor), and PI3K (Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase) were quantitatively measured via ELISA. Results showed a significant 2–3 fold increase in cell viability and proliferation in both Ishikawa and OVCAR3 cells following combined treatment with cytokines and estrogen (****p < 0.001). Our model recapitulates key biological processes underlying the malignant transformation of endometriosis. Furthermore, the study contributes to the literature by revealing the influence of microenvironmental factors in the transition from endometriosis to ovarian cancer. In conclusion, this study demonstrates the potential role of an estrogen and cytokine-driven endometriotic microenvironment in malignant transformation, highlighting molecular and cellular targets relevant to EAOC development. These findings suggest that this model could be applied to future studies using primary human cells and provide a foundation for developing translational experimental systems with clinical relevance.

Keywords: Endometriosis, inflammation, cytokines, ovarian cancer, EAOC.

Abbreviations:

EAOC – Endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer

E2 – Estradiol

EGF – Epidermal growth factor

IL – Interleukin

IL-1β – Interleukin-1 beta

IL-6 – Interleukin-6

IL-10 – Interleukin-10

MTT – 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

NGF – Nerve growth factor

OD – Optical density

PI3K – Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

VEGF – Vascular endothelial growth factor

Introduction

Endometriosis is a chronic, estrogen-dependent gynecological disease histologically characterized by the presence of endometrial glands and stroma located in anatomical sites outside the uterine cavity. Its primary clinical manifestations include chronic pelvic pain and infertility.[1,2] Endometriosis may cause severe chronic pelvic pain in women of reproductive age.[2,3] Lesions can also be found in asymptomatic women and are detected in up to 50% of women undergoing infertility treatment.[4] Epidemiological studies report that women with endometriotic lesions are at increased risk for ovarian and breast cancer, melanoma, asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, and cardiovascular disease.[5,6,7]

Classically, an endometriotic lesion resembles uterine endometrial tissue. The eutopic endometrium, a dynamic, hormone-responsive tissue of epithelial and stromal cells with rich vasculature and immune populations, makes comparing eutopic and ectopic tissue important. During menstruation, the surface layer of this tissue breaks down and sheds.[8-9]

Although endometriosis is often called “estrogen-dependent,” recent studies suggest it is “steroid-dependent,” since various steroid hormones and their receptors regulate both eutopic and ectopic endometrium. The continuity and progression of endometriotic lesions strictly depend on angiogenesis. Related studies have shown that angiogenic factors such as VEGF-A and NRP-1 are significantly increased in ectopic tissues and peritoneal fluid.[10.11]

Neuroangiogenesis (coordinated nerve and blood vessel growth) and neuroinflammation play key roles in endometriosis-related pain. Clinical and experimental studies show that inflammation initiates these processes, leading to simultaneous neural and vascular development and increased peripheral and central sensitization. Ectopic lesions can form their own neurovascular networks, which correlate with chronic pelvic pain.[12]

According to the retrograde menstruation theory, endometrial cells shed during menstruation pass through the fallopian tubes into the peritoneal cavity, where they adhere and form ectopic lesions. During this process, adhesion, invasion, proliferation, and vascular support are required. Various cells—especially macrophages and stromal cells in the peritoneum—contribute to the formation of an inflammatory environment that supports lesion progression. Cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α are key factors promoting adhesion and invasion.

Macrophages play a central role in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Activated macrophages are found in higher numbers in the peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis and secrete high levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and VEGF. These factors support lesion adhesion, proliferation, and angiogenesis, contributing to disease progression. Considering immune tolerance loss, inflammation, and oxidative stress together helps better explain the link between endometriosis and malignant transformation.

The relationship between endometriosis and malignant transformation is particularly significant in the context of endometrioid and clear cell ovarian cancers (EAOC).[3,6,13] Inflammation, oxidative stress, epigenetic changes, and genetic mutations have all been implicated in the development of EAOC. For example, Linder et al. (2024) have demonstrated that immune-related genes undergo early mutations in both endometriosis and EAOC. These findings suggest that inflammatory cytokines in endometriosis play critical roles in both disease progression and potential malignant transformation.

To model endometriosis at the cellular and molecular level, various in vitro systems have been developed. Commonly used cell models include human endometrial epithelial cell lines (e.g., 12Z and Ishikawa), stromal cell lines (e.g., St-T1b and primary endometriotic stromal cells), and primary endometrial cultures. Co-culture systems have been used to study epithelial-stromal interactions, and cellular responses to hormones and inflammatory stimuli have been extensively analyzed in these models. Three-dimensional (3D) culture systems, such as spheroid and organoid technologies, offer more physiologically relevant representations of the morphological and functional features of ectopic endometriotic lesions. These models allow for experimental investigation of key mechanisms in disease pathogenesis, including angiogenesis, invasion, proliferation, and immune response.[15,16]

Ishikawa cells, derived from well-differentiated human endometrial adenocarcinoma, are a cell line that functionally retains estrogen and progesterone receptors. [14] They reflect normal endometrial functionality in terms of estrogen-induced progesterone receptor expression and progesterone-mediated suppression. Although they do not completely mimic endometriotic tissue, they express many structural proteins and enzymes found in endometrial glands, making them a valid model for studying endometrial function. Genes expressed in Ishikawa cells treated with E2 and P4 overlap by 98–99% with those in human endometrial samples, supporting the translational validity of this model.[17]

Studies using endometrial cell culture models have shown significant increases in the expression of MMP-2, MMP-9, VEGF, VEGFR-1, -2, and -3, as well as IL-1β and TNF-α.[18] Endometriotic lesions are characterized by marked vascularization and significantly elevated VEGF levels in the peritoneal fluid.[20,21] An increasing number of studies suggest multiple mechanisms contribute to the vascularization of endometriotic lesions.

In this study, our central hypothesis is that estrogen and pro-inflammatory cytokines (particularly IL-6, VEGF, and EGF) present in the endometriotic microenvironment enhance the proliferation, invasion, and angiogenic capacity of ovarian cancer cells, thereby promoting malignant transformation.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

The Ishikawa endometrial adenocarcinoma cell line (HTB-112) and the OVCAR3 ovarian cancer cell line (HTB-161™), both obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Maryland, Rockville), were used in this study. The cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (DMEM-HA, Capricorn, Germany) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (FBS-16A, Capricorn, Germany) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (PS-B, Capricorn, Germany). Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO₂. All experiments were conducted when cells reached 80–90% confluency, and their growth and morphology were regularly monitored by phase-contrast microscopy.

Hormone and Cytokine Treatment and Cell Viability Assay

For hormonal and cytokine stimulation, 105 cells/ well were transferred into DMEM supplemented with 1% serum and allowed to pre-incubate for 24 hours. Then, cells were treated with the following factors: EGF (0.1 µg/mL), IL-6 (0.1 µg/mL), IL-1β (5 ng/mL), VEGF (0.1 µg/mL), IL-10 (0.1 µg/mL), and estrogen (10 nM). The concentrations used were chosen to reflect physiological doses. After 48 hours of incubation, cell viability was assessed using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5‑diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) Cell Proliferation and Cytotoxicity Assay Kit (E-CK-A341, Elabscience, Texas USA). Specifically, 20 µL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL) was added to cells cultured in 96-well plates and incubated for 3 hours at 37°C. The resulting formazan crystals were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (D2650,Merck, Sigma, Germany), and absorbance was measured at 570 nm (wavelength) (using a microplate reader.[18]

Endometriosis Cell Model

The endometriosis-like in vitro model was established using Ishikawa cells. Cells were treated for 48 hours with a combination of estrogen (10 nM) and cytokines including EGF (0.1 µg/mL), IL-6 (0.1 µg/mL, IL-1β (5 ng/mL), VEGF (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor) (0.1 µg/mL), and IL-10 (0.1 µg) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). These conditions were validated to induce proliferative and inflammatory responses that reflect an endometriosis-like microenvironment. The model’s validity was confirmed by cell viability assays using MTT and by quantifying VEGF secretion, an inflammatory marker, via ELISA.[19]

Model Validation

To validate the in vitro endometriosis model, VEGF levels in the culture supernatants from treated cells were quantified using a commercially available VEGF ELISA kit (BD Biosciences,). Supernatants were added to 96-well plates pre-coated with anti-VEGF antibodies. According to the kit protocol, washing steps, binding of detection antibodies, and color development reactions were performed. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm with a microplate reader, and VEGF concentrations were calculated using a standard curve.

Treatment of OVCAR3 Cells with Endometriotic Microenvironment

OVCAR3 cells were exposed for 48 hours to conditioned media derived from Ishikawa cells that had been previously treated with cytokines, estrogen, or their combination. To prepare the endometriosis-like microenvironment, the supernatants of treated Ishikawa cells were centrifuged and diluted 1:1 with fresh medium containing 10% FBS. OVCAR3 cells were cultured in this conditioned medium. This treatment aimed to evaluate the effects of inflammatory and hormonal factors derived from the endometriotic environment on ovarian cancer cells. After 48 hours of exposure, cell proliferation, viability, and secretion of angiogenic factors were analyzed.

Unless otherwise specified, all chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Results

In this study, an in vitro endometriosis model was established, and the microenvironment generated by this model was used to treat the OVCAR3 cell line in order to investigate the cellular consequences of this interaction. Data obtained from the endometriosis cell model and from the exposure of OVCAR3 cells to the endometriosis microenvironment were comprehensively evaluated in terms of cell viability, proliferation, and inflammatory responses. Cell proliferation was assessed using the MTT assay, and VEGF levels in the culture supernatants were quantified by ELISA. The findings demonstrate that hormone and cytokine treatments influence the biological behavior of the cells, providing important insights into the potential relationship between endometriosis and ovarian cancer cells.

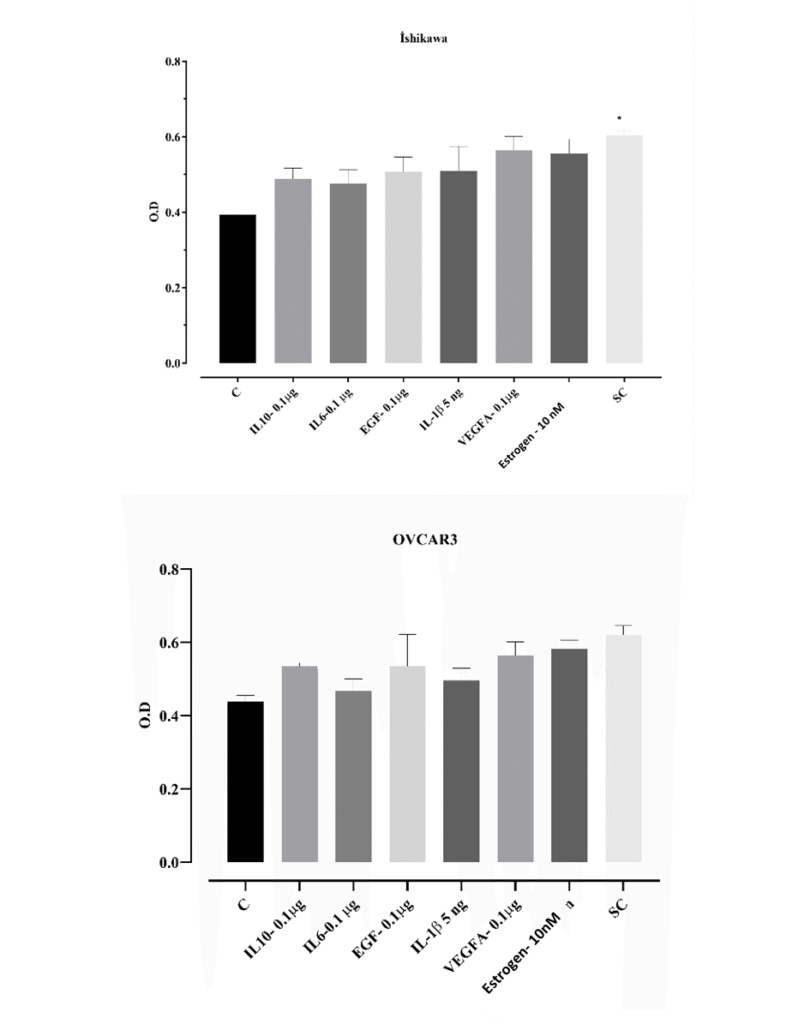

Cellular Responses in the Endometriosis Model

Ishikawa cells were treated for 48 hours with various cytokines and growth factors including EGF, IL-6, IL-10 (10 µg/mL), IL-1β (5 ng/mL), VEGF (0.1 µg/mL), and estrogen (10 nM). Cell viability was assessed using the MTT assay. All treatment groups showed increased cell viability compared to the control group, with the cytokine cocktail group (SK: cytokines + EGF + estrogen) showing statistically significant enhancement (*p<0.05). These findings suggest that individual factors may promote proliferation, but their combined application may produce a synergistic proliferative effect.

Similarly, OVCAR3 cells were exposed to EGF, IL-6, IL-10 (10 µg/mL), IL-1β (5 ng/mL), VEGF (0.1 µg/mL), and estrogen (10 nM) for 48 hours. The MTT assay revealed increased viability in all treated groups compared to the control, with the SC group showing the highest response. This indicates that OVCAR3 cells also exhibit a proliferative response in the presence of cytokines and estrogen. Collectively, these results demonstrate that both Ishikawa and OVCAR3 cells respond positively to inflammatory and growth factors in terms of viability (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Cell viability in Ishikawa and OVCAR3 cells in response to cytokine and growth factor treatment. Cells were treated with EGF (0.1 µg/mL), IL-6 (0.1 µg/mL), IL-1β (5 ng/mL), VEGF (0.1 µg/mL), IL-10 (0.1 µg/mL), and estrogen (10 nM) at concentrations of 0.1 and 1 µg/mL (cytokines, estrogen, and EGF included in the SC group). After 48 h, cell viability was assessed using the MTT assay. Cell viability was quantitatively determined by optical density (OD) measurements, and data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (n =3). *p < 0.05; statistically significant compared to the control group.

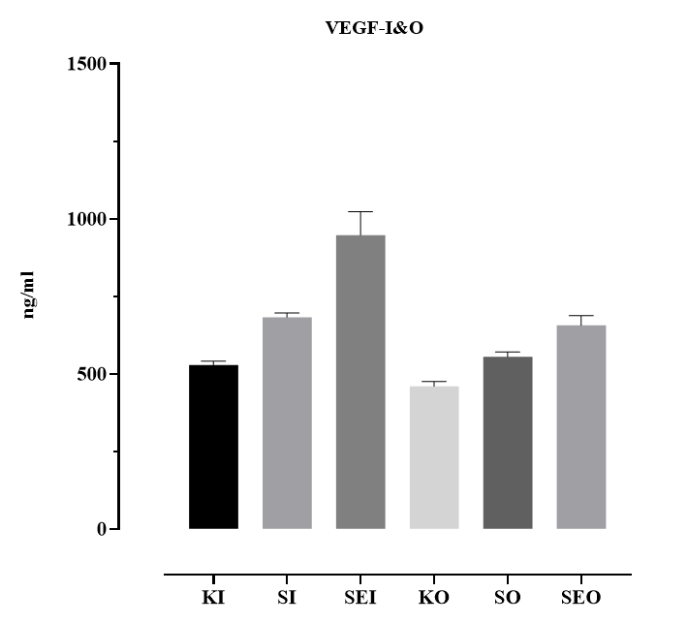

An increase in VEGF secretion was observed in Ishikawa and OVCAR3 cells exposed to an endometriosis-like microenvironment (Figure 2). This increase indicates that the endometriosis milieu activates the angiogenic response and that the cells exhibit a biological reaction to microenvironmental inflammatory stimuli. Together with the cell count results, this finding supports the biological validity of the model in mimicking endometriosis.

Figure 2. VEGF secretion levels in Ishikawa and OVCAR3 cells following hormone and cytokine treatment. Cells were treated for 48 h with EGF (0.1 µg/mL), IL-6 (0.1 µg/mL), IL-1β (5 ng/mL), VEGF (0.1 µg/mL), IL-10 (0.1 µg/mL), and estrogen (10 nM) at concentrations of 0.1 and 1 µg/mL. (KI: control Ishikawa; SI: cytokines Ishikawa; SEI: cytokines and estrogen Ishikawa; CO: control OVCAR3; SO: cytokines OVCAR3; SEO: cytokines and estrogen OVCAR3). VEGF levels in the supernatants were measured using the ELISA method and expressed in ng/mL. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3).

Ishikawa cells were treated with various growth factors (EGF, VEGF) and cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10) at concentrations of 0.1 and 1 µg/mL for 48 h, and cell viability was assessed using the MTT assay. The results showed that VEGF markedly increased cell viability at both doses, yielding the highest optical density (OD) values in the MTT assay. IL-1β similarly promoted proliferation, with a more pronounced effect at 0.1 µg/mL. IL-6 reduced cell viability at the lower dose, but this effect was reversed at 1 µg/mL. EGF increased cell viability, although the magnitude of this effect was more limited compared to VEGF and IL-1β. The anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, particularly at the higher dose, decreased cell viability. The control group displayed the lowest OD values, indicating limited proliferation in the absence of cytokine or growth factor stimulation. These findings suggest that certain factors present in the endometriosis microenvironment can directly influence the proliferation of endometrial cells.

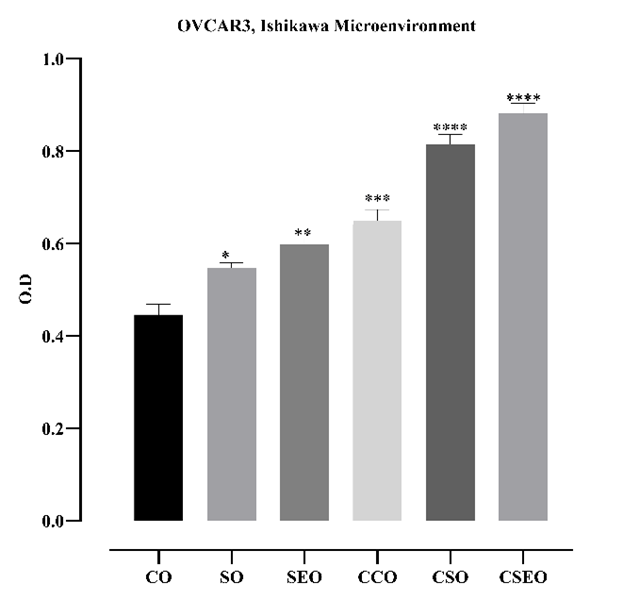

Responses of OVCAR3 Cells to the Endometriosis Microenvironment

When the proliferation of OVCAR3 cells treated with cytokines and estrogen was compared to that of OVCAR3 cells exposed for 48 h to an endometrium-like microenvironment, the increase observed in the microenvironment-treated group indicated that these cells biologically respond to endometriosis conditions. The marked elevation in cell proliferation within the cytokine-enriched environment further supports the notion that the endometriosis microenvironment may stimulate the growth of ovarian cells (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Effect of a 48-h treatment with the microenvironment derived from Ishikawa cells in the endometriosis model on the viability of OVCAR3 cells. Cell viability was assessed using the MTT assay, and optical density (OD) values were plotted (CO: control OVCAR3; SO: cytokines OVCAR3; SEO: cytokines + estrogen OVCAR3; CCO: microenvironment control OVCAR3; CSO: microenvironment + cytokines OVCAR3; CSEO: microenvironment + cytokines + estrogen OVCAR3). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 4). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001; statistically significant compared to the control group.

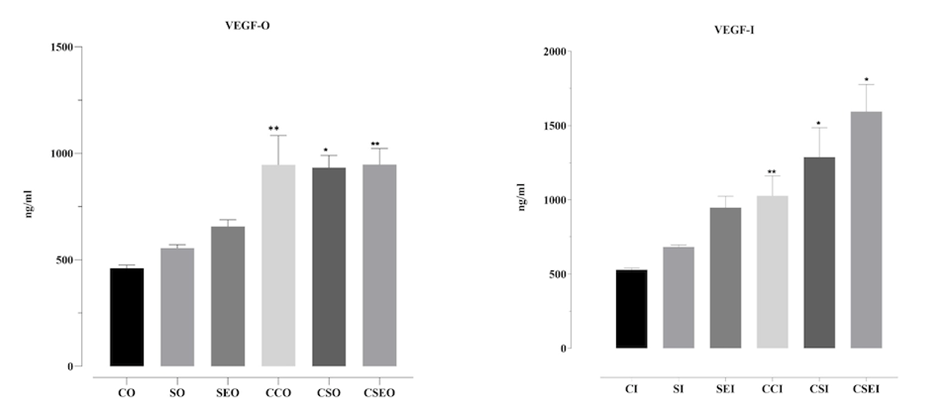

VEGF secretion in OVCAR3 (O) and Ishikawa (I) cells treated with the endometriosis microenvironment for 48 h was evaluated using the ELISA method. In Ishikawa cells, ELISA analysis of VEGF secretion revealed an increase in the groups exposed to an endometriosis-like microenvironment. While VEGF levels remained low in the control group, a gradual increase was observed with cytokine (SO) and cytokine + estrogen (SEO) treatments. In the controlled microenvironment groups (CCO, CSO, CSEO), a marked increase was detected, particularly in the CSEO group, in which VEGF levels reached approximately 1000 ng/mL. These findings indicate that the combined application of cytokines and estrogen within a controlled microenvironment synergistically enhances VEGF secretion and effectively mimics the angiogenic response in the endometriosis model.

In OVCAR3 cells, VEGF levels in the control group (CO) were the lowest, at approximately 500 ng/mL. Partial increases were observed with cytokine (SO) and cytokine + estrogen (SEO) treatments, whereas controlled microenvironment applications (CCO, CSO, CSEO) resulted in a significant elevation in VEGF secretion. Notably, the CCO group reached VEGF concentrations close to 21,000 ng/mL, a statistically significant increase (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). Similarly, the CSEO group also exhibited markedly high VEGF levels (Figure 4).

Figure 4. VEGF secretion levels in OVCAR3 and Ishikawa cells treated with the endometriosis microenvironment for 48 h. CO: control OVCAR3; SO: cytokines OVCAR3; SEO: cytokines + estrogen OVCAR3; CCO: microenvironment control OVCAR3; CSO: microenvironment + cytokines OVCAR3; CSEO: microenvironment + cytokines + estrogen OVCAR3. The groups labeled with the suffix ‘I’ represent the corresponding experimental conditions in Ishikawa cells. VEGF concentrations measured by ELISA are presented in comparison with the control group. Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, statistically significant compared to the control group.

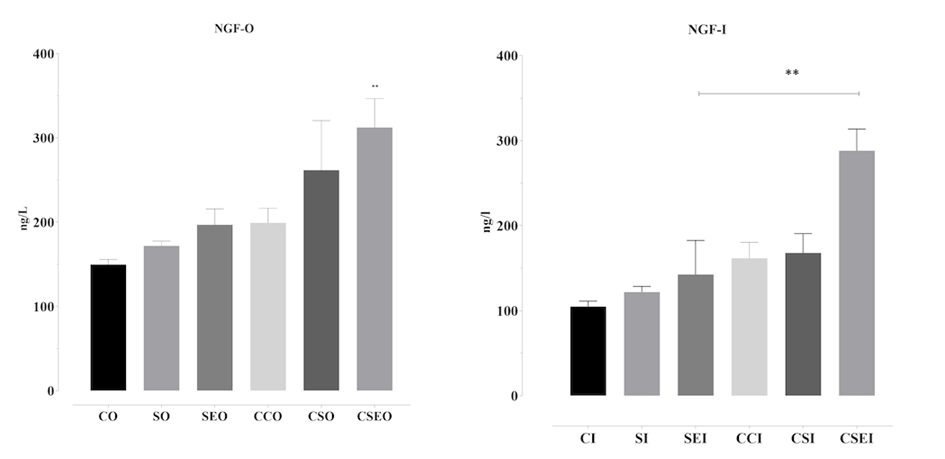

NGF levels in OVCAR3 (PI3K-O) and Ishikawa (PI3K-I) cells treated with the endometriosis microenvironment for 48 h were quantitatively evaluated using the ELISA method. The highest NGF level was detected in the CSEO group, in which cytokines and estrogen were applied together, and this increase was statistically significant compared to the control group (**p < 0.01). This finding indicates that the combination of estrogen and cytokines synergistically stimulates NGF production in epithelial cells. In contrast, NGF levels in the SEO group, which contained only estrogen, remained low, suggesting that estrogen alone may limit or suppress NGF secretion in this cell type. Overall, the endometriosis microenvironment significantly influences NGF production in Ishikawa cells, depending on the nature of the cellular response and the specific components of the microenvironment.

In OVCAR3 cells, NGF secretion levels varied significantly among the groups. Notably, the CSEO group exhibited a statistically significant increase in NGF levels compared to the control group (p < 0.01), indicating that the combination microenvironment most strongly stimulates NGF production. Similarly, the CSO group showed high NGF secretion, supporting the predominant effect of cytokines. Conversely, NGF levels in the SEO group, containing only estrogen, were markedly lower, further suggesting that estrogen alone may suppress NGF production. These findings demonstrate that the endometriosis microenvironment can modulate NGF production in ovarian-derived cells to varying degrees depending on the factors it contains (Figure 5).

Figure 5. NGF secretion levels in OVCAR3 and Ishikawa cells treated with the endometriosis microenvironment for 48 h. CO: control OVCAR3; SO: cytokines OVCAR3; SEO: cytokines + estrogen OVCAR3; CCO: microenvironment control OVCAR3; CSO: microenvironment + cytokines OVCAR3; CSEO: microenvironment + cytokines + estrogen OVCAR3. The groups labeled with the suffix ‘I’ represent the corresponding experimental conditions in Ishikawa cells. NGF levels in cell supernatants were quantitatively measured using the ELISA method and plotted as graphs. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; statistically significant compared to the control group.

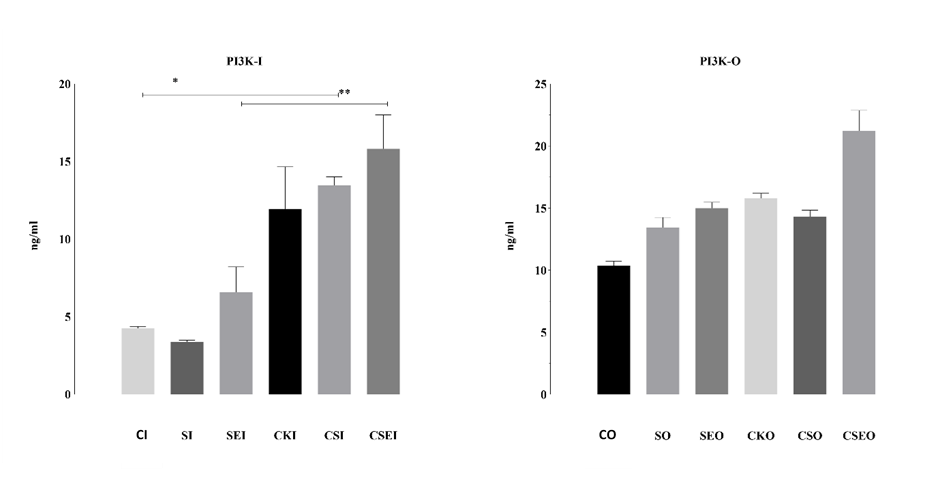

PI3K levels in OVCAR3 (PI3K-O) and Ishikawa (PI3K-I) cells treated with the endometriosis microenvironment for 48 h were quantitatively evaluated using the ELISA method. In Ishikawa cells, 48-h exposure to the endometriosis microenvironment resulted in significant differences in PI3K secretion. The highest PI3K level was detected in the SI group, which received cytokines alone, and this increase was statistically significant compared with the control group (p < 0.05). This finding indicates that cytokines can directly activate the PI3K pathway in epithelial cells. In contrast, the SEI group, which contained estrogen, showed a marked reduction in PI3K levels, suggesting that estrogen may exert an inhibitory effect on this signaling pathway under certain conditions. These results demonstrate that the components of the endometriosis microenvironment can differentially influence PI3K secretion in Ishikawa cells, with potential implications for processes such as cellular proliferation, viability, and survival.

In OVCAR3 cells, PI3K secretion levels varied significantly among the groups, with particularly notable increases in the CSO and CSEO groups compared with the control group (**p < 0.05, p < 0.01). The highest PI3K level was observed in the CSEO group, indicating that combined cytokine and estrogen treatment synergistically activates the PI3K pathway. This increase highlights that the PI3K signaling pathway—known to play a critical role in the regulation of cell proliferation, viability, survival, and inflammatory responses—is strongly triggered in an endometriosis-like microenvironment, particularly under combination stimulation. In contrast, the SEO group, which contained only estrogen, exhibited relatively low PI3K levels, suggesting that estrogen alone is insufficient to elicit a robust response. Collectively, these findings indicate that the endometriosis microenvironment can modulate PI3K activation depending on its components, thereby shaping the biological responses of ovarian cells (Figure 6).

Figure 6. PI3K secretion levels in OVCAR3 and Ishikawa cells treated with the endometriosis microenvironment for 48 h. CO: control OVCAR3; SO: cytokines OVCAR3; SEO: cytokines + estrogen OVCAR3; CCO: microenvironment control OVCAR3; CSO: microenvironment + cytokines OVCAR3; CSEO: microenvironment + cytokines + estrogen OVCAR3. The groups labeled with the suffix ‘I’ represent the corresponding experimental conditions in Ishikawa cells. PI3K concentrations measured by ELISA are presented in comparison with the control group. Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; statistically significant compared to the control group.

The findings of this study demonstrate that an endometriosis-like microenvironment induces significant changes in NGF, VEGF, and PI3K secretion levels, depending on cell type and microenvironmental composition. A microenvironment generated through the combination of cytokines and estrogen markedly enhanced the secretion of proinflammatory and angiogenic factors such as NGF and VEGF in both OVCAR3 and Ishikawa cells. Similarly, the observed increase in PI3K levels indicates activation of intracellular signaling pathways under these conditions. The pronounced elevation in VEGF levels suggests that the model effectively mimics the angiogenic response at the biological level. The increase in NGF levels further reveals that the neuroinflammatory processes characteristic of endometriosis are also active in this cell model. In addition, the rise in PI3K levels indicates activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, which is known to be associated with endometriosis, thereby effectively stimulating intracellular proliferative signaling networks.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software version 7.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). For comparisons among more than two groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was applied. For comparisons between two groups, unpaired Student’s t-tests were used. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from 3–5 independent experiments. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Discussion

Recent studies have shown that endometriosis is not merely an accumulation of ectopic endometrial tissue, but rather a complex microenvironment shaped by pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. This microenvironment promotes disease progression by supporting proliferation, invasion, and angiogenesis through epithelial and stromal cells.[22,23,24].

In this study, we evaluated the cellular responses of Ishikawa and OVCAR3 cells to an endometriosis-like microenvironment created using estrogen and a panel of cytokines. Our findings demonstrated that this microenvironment enhances epithelial cell viability, angiogenesis, and intracellular growth signaling. MTT assays confirmed increased proliferative activity in cells exposed to this microenvironment. These findings are consistent with clinical data showing increased proliferation in endometriotic tissues.[25,26]

Women with endometriosis have a 4.2-fold higher risk of developing ovarian cancer compared to those without the disease. In women with ovarian endometriomas and/or deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE), this risk increases up to 9.7-fold.[3,5,6] When examining associations between endometriosis subtypes and ovarian cancer histological subtypes, the strongest correlation is observed with Type I tumors (endometrioid, clear cell, mucinous, and low-grade serous), whereas the association is weaker for Type II (high-grade serous) tumors.[13,27,28,29]

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) plays a critical role in angiogenesis. In endometriosis patients, peritoneal fluid VEGF concentrations are elevated and correlate with disease severity.[30,31,32] As shown in Figure 4, VEGF levels were significantly increased in our model, supporting its ability to replicate the angiogenic response of endometriotic tissues.

Similarly, nerve growth factor (NGF), frequently associated with chronic pelvic pain in endometriosis patients, was elevated in response to the microenvironment in our study. As shown in Figure 5, NGF secretion was significantly increased, in line with previous reports of NGF overexpression in human endometriotic lesions.[33,34]

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway has been implicated in endometriosis-related lesion growth, cellular proliferation, and resistant phenotypes. Estrogen-induced activation of this pathway has been linked to increased proliferation, angiogenesis, and invasion, whereas inhibition reduces cell proliferation significantly.[35,36] In line with these findings, our model also demonstrated significantly increased PI3K levels (Figure 6), confirming the activation of this pathway.

This study was conducted to evaluate the proliferative, inflammatory, and angiogenic effects of an in vitro endometriosis-like microenvironment on ovarian cancer cells. Although our findings indicate that this microenvironment exerts tumor-promoting effects, certain limitations should be noted. These include the use of established cell lines instead of primary endometrial epithelial cells and the limited range of cytokines and growth factors assessed. Despite these limitations, the data obtained provide a valuable basis for future, more comprehensive studies employing translational approaches.

Our experiments demonstrate that an in vitro–generated endometriosis-like microenvironment promotes proliferation, inflammation, and angiogenesis in ovarian cancer cells. Overall, this work highlights the potential contribution of estrogen- and cytokine-based endometriosis microenvironments to malignant transformation and may help identify molecular and cellular targets relevant to the development of endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer (EAOC). The results also indicate that this model could be adapted for use with primary human cells in future research, paving the way for experimental systems that may be translated into clinical applications. In summary, this preliminary model comprehensively characterizes the cellular responses induced by an endometriosis-like microenvironment and demonstrates consistency with existing human data.

Conclusion

Our findings provide novel insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying endometriosis-associated malignancy, particularly the roles of VEGF, NGF, and PI3K signaling pathways. By demonstrating these associations, the study emphasizes how angiogenic and neurogenic factors may converge to drive disease progression. The in vitro model established here offers a valuable experimental platform that can be adapted to explore additional pathways and therapeutic interventions. Importantly, when complemented with studies using patient-derived tissues, this model has the potential to bridge the gap between basic research and clinical application, thereby advancing both our mechanistic understanding of the disease and the development of translational strategies for improved diagnosis and treatment.

Acknowledges

This study was derived from the Master’s theses titled “The Effects of Inflammation Factors and Epidermal Growth Factor Associated with Endometriosis on the Development of Ovarian Cancers” and “The Effects of Micro-Needles Containing Lactobacillus and Prevotella Microenvironments on Carcinogenesis in Endometrial Cell Lines”, prepared at the Institute of Health Sciences, Marmara University.

Author Contributions

Tuğba Çevik: Writing – original draft, methodology, conducting experiments

Gizem Ayermolalı: Conducting experiments, formal analysis, contribution to the final version of the manuscript

Zehra Kanlı: Performing experiments, data collection, laboratory analyses

Burak Aksu: Contribution to laboratory analyses, data validation

Hülya Cabadak: Supervision

Tevfik Yoldemir: Supervision, clinical interpretation, final approval

Banu Aydın: Methodology, funding acquisition, statistical analysis, final approval of the manuscript

All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

This study’s datasets are not publicly available, but can be provided by the Corresponding Author under a reasonable request.

Disclosure Statement

Funding

This study was supported by Marmara University Scientific Research Projects Commission with project number 11435.

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics Committee Approval

This study does not involve direct experimentation on human or animal subjects; therefore, ethics committee approval was not required.

References

- Zondervan KT, Becker CM, Missmer SA. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1244–1256. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1810764.

- Viganò P, Parazzini F, Somigliana E, Vercellini P. Endometriosis: Epidemiology and aetiological factors. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;18(2):177–200. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2004.01.007.

- Yoldemir T. Evaluation and management of endometriosis. Climacteric. 2023;26(3):248–255. doi:10.1080/13697137.2023.2190882.

- Meuleman C, Vandenabeele B, Fieuws S, Spiessens C, Timmerman D, D’Hooghe T. High prevalence of endometriosis in infertile women with normal ovulation and normospermic partners. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(1):68–74. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.04.056.

- Yoldemir T. MHT in menopausal women at risk: comorbidity endometriosis. Maturitas. 2019;124:119. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.04.030.

- Ozyurek ES, Yoldemir T, Kalkan U. Surgical challenges in the treatment of perimenopausal and postmenopausal endometriosis. Climacteric. 2018;21(4):385–390. doi:10.1080/13697137.2018.1439913.

- Kvaskoff M, Mu F, Terry KL, Harris HR, Poole EM, Farland LV, et al. Endometriosis: a high‑risk population for major chronic diseases? Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21(4):500–16. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmv013.

- Gibson DA, Simitsidellis I, Collins F, Saunders PTK. Androgens, oestrogens and endometrium: a fine balance between perfection and pathology. J Endocrinol. 2020;246(3):57–73. doi:10.1530/JOE‑20‑0106.

- Wang Y, Nicholes K, Shih IM. The origin and pathogenesis of endometriosis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2020;15:71–95.

doi:10.1146/annurev‑pathmechdis‑012419‑032655.

- Nap AW, Griffioen AW, Dunselman GAJ, Bouma‑Ter Steege JC, Thijssen VL, Evers JLH, Groothuis PG. Antiangiogenesis therapy for endometriosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(3):1089–1095. doi:10.1210/jc.89.3.1089.

- Machado DE, et al. Higher expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors in peritoneal fluid and lesions of endometriosis patients. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2010;29(4). doi:10.1186/1756‑9966‑29‑4.

- Asante A, Taylor C, Horne AW. Endometriosis: the role of neuroangiogenesis. Annu Rev Physiol. 2011;73:163–182. doi:10.1146/annurev‑physiol‑012110‑142103.

- Yoldemir T. Postmenopausal endometriosis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2024;40(1):2441299. doi:10.1080/09513590.2024.2441299.

- Linder A, Westbom‑Fremer S, Mateoiu C, et al. Genomic alterations in ovarian endometriosis and subsequently diagnosed ovarian carcinoma. Hum Reprod. 2024; (Advance online publication). doi:10.1093/humrep/deae043.

- Gołąbek-Grenda A, Olejnik A. In vitro modeling of endometriosis and endometriotic microenvironment – Challenges and recent advances. Cell Signal. 2022 Sep;97:110375. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2022.110375. Epub 2022 Jun 9. PMID: 35690293.

- Kloeckner AA, et al. Endometriosis Cell Spheroids Undergo Mesothelial Clearance in a 3D Model. Cells. 2025;14(10):742.

- Lessey BA, Ilesanmi AO, Castelbaum AJ, Yuan L, Somkuti SG, Chwalisz K, Satyaswaroop PG. Characterization of the functional progesterone receptor in an endometrial adenocarcinoma cell line (Ishikawa): Progesterone induced expression of the alpha1 integrin. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;59(1):31–39. doi:10.1016/S0960‑0760(96)00103‑3.

- Guldorum, Y. Et Al. 2024. Ethosuximide-loaded bismuth ferrite nanoparticles as a potential drug delivery system for the treatment of epilepsy disease. PLoS ONE , vol.19, no.9 .

- Tamm Rosenstein K, Simm J, Suhorutshenko M, Salumets A, Metsis M. Changes in the transcriptome of the human endometrial Ishikawa cancer cell line induced by estrogen, progesterone, tamoxifen, and mifepristone (RU486) as detected by RNA sequencing. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(7):e68907. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0068907.

- Zeitvogel A, Baumann R, Starzinski‑Powitz A. Identification of an invasive, N‑cadherin‑expressing epithelial cell type in endometriosis using a new cell culture model. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:1839–1852. doi:10.1016/S0002‑9440(10)63030.

- Banu SK, Lee J, Starzinski‑Powitz A, Arosh JA. Gene expression profiles and functional characterization of human immortalized endometriotic epithelial and stromal cells. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:972–987. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.07.1358.

- Hirata T, Osuga Y, Takamura M, Kodama A, Hirota Y, Koga K, Yoshino O, Harada M, Takemura Y, Yano T, et al. Recruitment of CCR6-expressing Th17 cells by CCL20 secreted from IL‑1β‑, TNF‑α‑, and IL‑17A‑stimulated endometriotic stromal cells. Endocrinology. 2010;151:5468–5476. doi:10.1210/en.2010‑0398.

- Guo P, Bi K, Lu Z, Wang K, Xu Y, Wu H, Cao Y, Jiang H. CCR5/CCR5 ligand‑induced myeloid‑derived suppressor cells are related to the progression of endometriosis. Reprod Biomed Online. 2019;39:704–711. doi:10.1016/j.rbmo.2019.05.014.

- Wu Y, Zhu F, Sun W, Shen W, Zhang Q, Chen H. Knockdown of CCL28 inhibits endometriosis stromal cell proliferation and invasion via ERK signaling pathway inactivation. Mol Med Rep. 2022;25(2):56. doi:10.3892/mmr.2021.12573.

- Kobayashi H, Kajiwara H, Kanayama S, Yamada Y, Furukawa N, Noguchi T, Oi H. Molecular pathogenesis of endometriosis‑associated clear cell carcinoma of the ovary. Oncol Rep. 2009;22(2):233–240.

- Liu J, Wang Y, Chen P, Ma Y, Wang S, Tian Y, Wang A, Wang D. AC002454.1 and CDK6 synergistically promote endometrial cell migration and invasion in endometriosis. Reproduction. 2019;157:535–543. doi:10.1530/REP‑19‑0005.

- Barnard ME, Farland LV, Yan B, Wang J, Trabert B, Doherty JA, Meeks HD, Madsen M, Guinto E, Collin LJ, Maurer KA, Page JM, Kiser AC, Varner MW, Allen‑Brady K, Pollack AZ, Peterson KR, Peterson CM, Schliep KC. Endometriosis Typology and Ovarian Cancer Risk. JAMA. 2024;332(6):482–489. doi:10.1001/jama.2024.9210.

- Kvaskoff M, Mahamat‑Saleh Y, Farland LV, Shigesi N, Terry KL, Harris HR, Roman H, Becker CM, As‑Sanie S, Zondervan KT, Horne AW, Missmer SA. Endometriosis and cancer: a systematic review and meta‑analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2021;27(2):393–420. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmaa045.

- Steinbuch SC, Lüß AM, Eltrop S, Götte M, Kiesel L. Endometriosis‑Associated Ovarian Cancer: From Molecular Pathologies to Clinical Relevance. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(8):4306. doi:10.3390/ijms25084306.

- McLaren J, Prentice A, Charnock‑Jones DS, Smith SK. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) concentrations are elevated in peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:220–223.

- Liu S, Xin X, Hua T, Shi R, Chi S, Jin Z, et al. Efficacy of Anti‑VEGF/VEGFR agents on animal models of endometriosis: a systematic review and meta‑analysis. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0166658. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0166658.

- Li WN, Hsiao KY, Wang CA, Chang N, Hsu PL, Sun CH, Wu SR, Wu MH, Tsai SJ. Extracellular vesicle‑associated VEGF‑C promotes lymphangiogenesis and immune cells infiltration in endometriosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(41):25859–25868. doi:10.1073/pnas.1920037117.

- Liu D, Liu M, Yu P, Li H. Brain‑derived neurotrophic factor and nerve growth factor expression in endometriosis: A systematic review and meta‑analysis. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2023;62(5):634–639. doi:10.1016/j.tjog.2023.07.003.

- Sreya M, Tucker DR, Yi J, Alotaibi FT, Lee AF, Noga H, Yong PJ. Nerve Bundle Density and Expression of NGF and IL‑1β Are Intra‑Individually Heterogenous in Subtypes of Endometriosis. Biomolecules. 2024;14(5):583. doi:10.3390/biom14050583.

- Driva TS, Schatz C, Haybaeck J. Endometriosis-Associated Ovarian Carcinomas: How PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway Affects Their Pathogenesis. Biomolecules. 2023 Aug 16;13(8):1253. doi: 10.3390/biom13081253. PMID: 37627318; PMCID: PMC10452661.

- Nakamura A, Tanaka Y, Amano T, Takebayashi A, Takahashi A, Hanada T, Tsuji S, Murakami T. mTOR inhibitors as potential therapeutics for endometriosis: a narrative review. Mol Hum Reprod. 2024 Dec 11;30(12):gaae041. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gaae041. PMID: 39579091; PMCID: PMC11634386.